I’ve been asked if I cook as well as I write about cooking.

It’s a fair question: I’ve been cooking almost as long as I’ve been writing. Writing was something I fell into, much like Alice down the rabbit-hole, when I was fourteen. I sat down one day to write myself a story instead of reading one, and thirty-two pages later—pencil and lined paper tablet—I finished my tale and realized that my predictable world had expanded wildly, enormously, with endlessly diverging and intriguing paths running every which way into an unknown I suddenly knew existed. Having ended one story (which is locked away, guarded by dragons and evil-eyed basilisks, and will never see the light of day if I have anything to say about it), I wanted to start all over again on another.

When or why I decided I needed to inflict culinary disasters on my long-suffering family and others, I don’t remember.

My most vivid cooking memory, even after so many years, is setting my brother on fire with my Cherries Jubilee.

I think I wanted to make Cherries Jubilee because of its name. Who wouldn’t? My mother made wonderful cherry pies for years. This was sort of the same thing only without a crust and with a match. A sauce for vanilla ice cream: how hard could that be? Just about all I had to do was pour a shot glass or two of brandy on some warmed cherries and light it up. As Shakespeare put it: “Strange how desire doth outrun performance.” As I ladled cherries into my youngest sibling’s bowl, my hand shook and suddenly there was a blue flame dancing along his blue jeans. I stared at it. He stared at it. The expression on his face mingled amazement that I had set him on fire with a long-suffering lack of surprise. For that one second, both of us wondered what to do. Then I decided: Better me than my brother. I brushed the flame off his knee with my hand and found that fire could be quite cool. His expression changed: for once I had managed to impress him, though it certainly wasn’t with my cooking.

Around that time, I was inspired and decided to bake a cake for my younger sister’s birthday. I asked her what she would like, and she pointed to the cover of a cookbook in one of the Time-Life world cooking series I had started to collect.

“That.”

It was a lovely, fantasy gingerbread house with a steeply pointed roof swathed in snow-colored frosting and decorated with various cookies for roof shingles and pastel colored candies outlining walls and windows. Okay. I was game. How hard—well, yeah, maybe a bit, but it would be fun. The recipe called for making the cake batter three times, and cutting the cake sheets into different shapes to make the house. After that would come the fun part. And then of course the eating. I forget how long it took me to make, or how badly I trashed my mother’s kitchen. Things I should have taken note of at the time I ignored. Finished, it looked only vaguely like the wicked witch’s enticing sweets-covered cottage on the cookbook cover. But I had done my best, and it was going to get eaten soon enough. So I thought.

I think it was the amount of flour and honey involved in the recipe that I should have noticed some time before we sang “Happy Birthday” and I tried to cut the cake. It was like taking a knife—or a tooth—to a brick. There was no eating that birthday cake; it was meant for greater things, or would have been if I had been a better decorator. My sister decided she wanted to keep it anyway; it was her birthday and her gingerbread house. So she gave it a home on top of the chest of drawers in her bedroom. There it stayed for weeks, or maybe months, drooping slightly, loosing a cookie now and then, until one of the cats knocked it onto the floor and it was finally thrown away.

Cats and cakes combine in other memories, as when I made a chocolate cake (entirely edible) for my parents’ wedding anniversary. I frosted it with chocolate, and filched a jar of my father’s maraschino cherries he liked in his Manhattans. I cut the cherries in half and placed them decoratively all over the frosting on the top and sides of the cake. I left it on the table to be admired and went to do other important things. When I came back I saw the cat on the table gently picking the cherry halves off the cake and munching them down. I did the lightning thing with my hair and the thundery thing with my voice and the cat vanished. I contemplated the problem for a moment. Nobody else was around. I halved more cherries, stuck them on the empty spots on the chocolate, and everyone ate cake with enthusiasm, blissful in their ignorance.

Even after decades of cooking, disasters loom. I habitually set off our fire alarms when I fry crab cakes. Recently I had to wonder if our house guests might die either of possibly contaminated frozen corn in the corn muffins (it was nowhere on the government website of suspects, but maybe they just missed it), or the chopped bacon I forgot to cook first when combining it with diced tuna loin for fish cakes. My guests recklessly ignored my worries but left town on their feet and smiling. The one time I made chowder from clams that my husband Dave and I had actually foraged from the mudflats during a low tide, I managed to cook the clams to the consistency and bounciness of pencil erasers in the chowder. The less said about the Cherry-Berries on a Cloud a friend and I forced upon our long-suffering parents the better.

So, to answer the question: Yes. Sometimes. Maybe. Don’t bet on it. No. The best of my cooking is often on the next page of my novel, where the fans are always on and the cats are always elsewhere.

Originally published June 2016 as part of And Related Subjects.

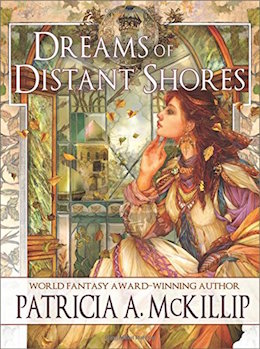

Patricia A. McKillip has published more novels than she can keep track of since 1973, most of them fantasy; The Book of Atrix Wolfe and Kingfisher both have a good deal of cooking in them. Her latest is Dreams of Distant Shores, a collection of stories. She lives on the southern Oregon coast with her husband, poet David Lunde.

Patricia A. McKillip has published more novels than she can keep track of since 1973, most of them fantasy; The Book of Atrix Wolfe and Kingfisher both have a good deal of cooking in them. Her latest is Dreams of Distant Shores, a collection of stories. She lives on the southern Oregon coast with her husband, poet David Lunde.